Pansori is a uniquely Korean music that lies somewhere between opera, spoken word and poetry and is accompanied by the beat of a “buk” drum. While it rose to popularity with the elite in the 19th century, Japanese occupation and westernization saw Pansori decline to a more folk status. Im Kwon-Taek’s film encapsulates Pansori’s position as a folk music, while also highlighting its significance as an expression of collective grief and national status, much like many other forms of folk music.

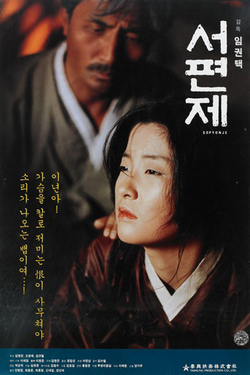

Seopyeonje follows a family of three traveling Pansori perfomers: Yu-Bong and his two children Dong-Ho and Song-Hwa. Once a highly acclaimed and successful performer of the art, Yu-Bong now struggles to make a living in the midst of the 1950s, where westernization and modernization prompts the decline in Pansori’s popularity. The relentless pressure Yu-Bong places on the two children to perform perfectly, especially the serene vocalist Song-Hwa, adds an emotional and painful tone to the film that is nonetheless captivating to watch. The film switches between the flashbacks of this family dynamic and the ‘present’ where, after eventually fleeing from his sister and father, Dong-Ho returns to the old villages years later in search of his sister. Without spoiling too much- it is the power of Pansori that both fractures and heals their relationship.

The film is punctured with Pansori and the music acts as a jack-of-all trades. It is everything from a character, a setting and a form of dialogue. It projects the suffering of Song-Hwa as she grows ill with longing for her brother, while at the same time it speaks of the glory of family and nationhood. Pansori itself, as it binds, yet breaks the family unit, serves as a metaphor for the state of Korea in the wave of westernization and modernization. The role of Pansori in Seopyeonje reminds us that our personal sufferings are also collective and political sufferings. Just like African-American work music and blues, and tunes of the 60s folk scene, Pansori, in its emotional and physical investment and driving power, provides the same tools of collective empowerment, complaint and protest.

(EMILY HOLLAND)